Never again will there be a man like George S. Patton. The four-star general wasn’t just a great man on the field of battle, he was also an inspiring paragon of American values and civic virtue, a tale of man’s will to overcome.

George Smith Patton Jr. was born on what would become Veteran’s Day, November 11, 1885 in San Gabriel, California. His father, George Smith Patton II, graduated from Virginia Military Institute on a scholarship but chose law over military service. Patton Jr. never seriously considered any other career path.

Despite being an avid reader, Patton struggled to learn how to read at an early age but was an otherwise excellent student at Stephen Clark’s School for Boys, a private school in Pasadena. He liked to read classical military histories. After spending two years at the Virginia Military Institute, he transferred to West Point where he continued to struggle with reading and writing, but excelled during inspections and drills.

While at West Point he earned the ranks of sergeant major during his junior year, and the cadet adjutant his senior year. He played football before an arm injury thrust him into the worlds of fencing and track and field.

In 1909, he graduated 46 out of 103 cadets and received a commission as a second lieutenant in the Cavalry branch of the United States Army.

Junior Officer George S. Patton

His first posting was with the 15th Cavalry at Fort Sheridan, Illinois. He quickly earned a reputation as a dedicated, driven leader of men. He became friends with Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, serving as his aide, as well as quartermaster of his troop.

In 1912, he competed in the modern pentathlon at the 1912 Olympics finishing in fifth place, behind four Swedes. He was the only American in the competition. All were military officers. As a junior officer, Patton served with distinction in the Pancho Villa campaign and even designed a new kind of sword for the cavalry. However, his country was about to go off to war and Patton was about to fall in love.

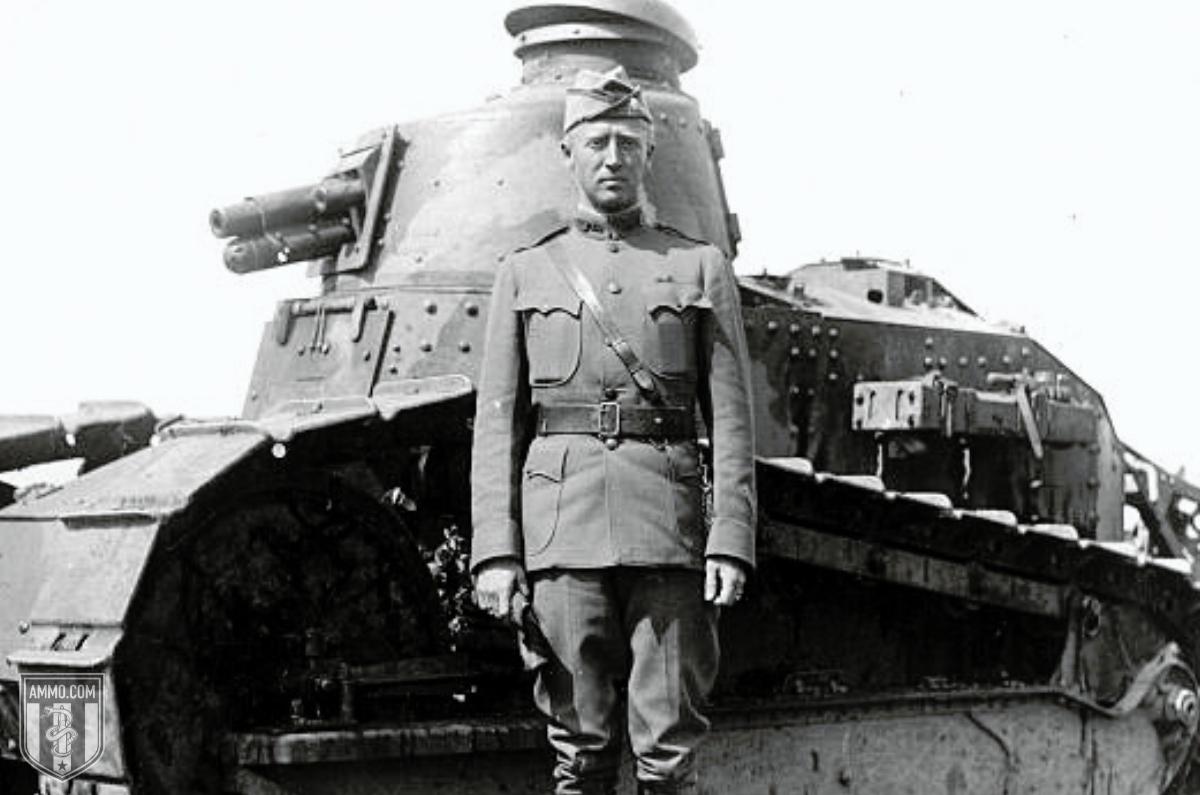

Patton’s Love Affair With the Tank

Patton was originally assigned to horse procurement stateside. But after the personal intervention of General John J. Pershing, Patton was sent to Europe as part of the American Expeditionary Force. Patton immediately became dissatisfied with the cavalry, taking an interest in tanks.

While in the hospital, Patton met Colonel Fox Conner, who encouraged him to work with tanks instead of infantry.

In 1917, Patton was assigned to establish the Army Expeditionary Force Light Tank School. He personally observed the manufacture of tanks and was promoted to major in 1918. When the school opened, Patton was the one to back the tanks off the delivery truck. Later in 1918, he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and attended the Command and General Staff College.

Upon its debut, Patton was placed in charge of the U.S. 1st Provisional Tank Brigade, part of the American First Army. Here, his bold command style was already making him something of a minor legend. He commanded his unit wounded from a shell hole for an hour, braining a man with a shovel and possibly killing him because he refused to work. He received the Distinguished Service Medal and the Distinguished Service Cross.

Patton Between the Wars

After the war, he was returned to his regular rank of captain, though he was promoted to major the next day. Commissioned to write a manual on tank operations, he became convinced of tanks as their own entity separate from infantry support.

Unfortunately, the Army did not move to create a serious tank corps until 1940. Much of Patton’s interwar years were spent in abject boredom, as he detested the life of a peacetime staff officer in the cavalry. While assigned to the Office of the Chief of Cavalry in Washington, D.C., Patton began to formulate his ideas of tank warfare.

The biggest event between the Wars for Patton was his encounter with the Bonus Army. This was an “army” of veterans who had marched on Washington to demand early payment of “war bonuses,” the returns on war bonds, during the Great Depression. Under orders from General MacArthur, Patton dispersed the group with tear gas and bayonets.

Patton was sympathetic to the Bonus Army’s demands, and he found the manner in which he dealt with them to be the most distasteful episode of his military career. However, he never expressed regret for breaking them up. Patton believed that the Bonus Army would have created an insurrection, resulting in violence and the destruction of property if unchecked.

Less known is Patton’s role in identifying Japanese aggression early on. While a lieutenant colonel in the Hawaiian Division, he wrote a paper on how to intern Japanese citizens in the event of a surprise attack by the Empire of Japan. Written in 1937, it was described as “chillingly accurate” after the Pearl Harbor attack.

Patton yearned for war. He eventually turned to drinking and an alleged affair with his 21-year-old niece by marriage. Accounts differ as to whether he was having an affair or simply trying to be boastful.

Patton’s Second World War

The United States military began mobilization in 1939. He made brigadier general on October 12, 1940 and major general in April of 1941. He was in charge of training one of the only divisions that centered around heavy tanks. Patton went so far as to earn a pilot’s license so that he could observe his tank formations from the air. During the Tennessee Maneuvers, he finished 48 hours of operations in nine.

In combat, Patton was known as an aggressive commander who always sought to keep pressure on the enemy front lines. He was widely admired by the men he commanded and earned a reputation as a fearsome general in the North African campaign. He was instrumental in the invasion of Sicily.

During the Sicily campaign, Patton became a bit of a figure of scorn in the media after he slapped a private under his command. The soldier claimed to be suffering from what was then called “battle fatigue,” but Patton believed him to be a goldbricker and slapped and verbally abused him. It is believed that this incident is why he did not lead the Allied invasion of France.

The Axis powers, however, firmly believed he would lead the invasion. So the Allies used him in decoy operations far away from the invasion site. In fact, the Ghost Army, as it was called, worked so well that the Axis believed they were fighting a diversionary force when confronted with the landing at D-Day.

Patton’s next big moment was at the Battle of the Bulge. After the Battle of the Bulge, Patton made quick progress into Germany.

After the War

Patton begged for action in the Pacific Theater, but General MacAruthur set the condition that Patton have a Chinese port secured for operations, an unlikely scenario. He was tapped for military governor of Bavaria. Upon learning of Japan’s surrender, Patton wrote “Yet another war has come to an end, and with it my usefulness to the world.”

Patton became depressed at the notion of no more battles to fight. He was relieved of command after a heated exchange with General Dwight Eisenhower, who is believed to have demanded his resignation. Upon being relieved of command, the always poetic Patton remarked “All good things must come to an end. The best thing that has ever happened to me thus far is the honor and privilege of having commanded the Third Army.”

On December 9, while on the way back from a pheasant hunting trip, Patton was killed in a car accident. He spent 12 days in traction before passing away, commenting “This is a hell of a way to die.” He died in his sleep from pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure at the age of 60.

Patton’s legacy is a mixed one. He was most feared and respected by the Axis generals, but the Allied generals often questioned his judgment. He spoke in a frank manner that rubbed many the wrong way and ultimately lead to his removal from command. He had a unique, brash style that was all his own, with his self-designed uniforms and ivory-handled pistols.

Patton is buried at the Luxembourg American Cemetery and Memorial in the Hamm district of Luxembourg City. This is in accordance with his request that he be buried with his men. He represents the best of America’s military traditions. We will never see his like again.

Written by Sam Jacobs. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Reproduced with kind permission. Original here.